- Home

- Jim Colucci

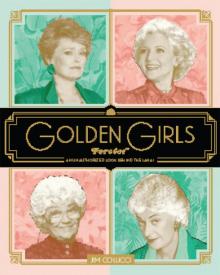

Golden Girls Forever

Golden Girls Forever Read online

DEDICATION

To

BEA ARTHUR,

RUE McCLANAHAN, BETTY WHITE,

and ESTELLE GETTY—

Thank You for Being

a Friend

CONTENTS

Dedication

1. Getting Started

2. Meeting (All): The Girls

3. Curtains Up

4. What Makes the Girls: So Golden

5. Golden Episodes

6. From Kitchen to Lanai: Production & Set Design

7. Miami, You’ve Got Style

Conclusion: The Girls are Still Golden Today

Thank you for Being a Friend

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Before the Girls were Golden, and after Miami was Nice, one of the alternate titles briefly considered was Ladies Day.

Photo courtesy of LEX PASSARIS.

1

GETTING STARTED

“Brandon always came up with these wacky ideas, and some of them were genius and some were terrible. That’s the sort of thing that happens with creative people who mine their inner child. You either get Mr. Smith, about the talking orangutan, or you get The Golden Girls.”

—GARTH ANCIER,

former head of current comedy at NBC

PICTURE IT: AUGUST 24, 1984. Two actresses “of a certain age,” each currently appearing on a hit NBC show, step out onstage at the network’s Burbank headquarters. As presenters at the network’s fall preview special, they trade scripted patter from a teleprompter, and in the process, do more than a little ogling of a male lead in one of the peacock network’s more promising new dramas. The object of their affection? None other than Mr. Don Johnson, then about to debut in the fashion- and decade-defining hit Miami Vice. And the gawking gals, whose performance that night would inspire NBC president Brandon Tartikoff to commission a sitcom about the active lives and loves of the over-sixty set? They are, of course . . . Selma Diamond and Doris Roberts.

What, you were expecting Bea Arthur or Betty White?

The tale of how one of the most beloved comedies of all time made its way to the small screen is not a straightforward one, nor is it very likely.

Miami Nice

IN TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY TV land, we may have more channels to choose from, but some things haven’t really changed since 1985; then, as now, broadcast networks like NBC aimed their programming squarely at the advertiser-coveted 18-49 age demographic. So that night at the NBC presentation, when Selma Diamond, who was then appearing on the network’s Thursday night sitcom Night Court, stopped eyeballing Don Johnson long enough to excitedly tell Remington Steele’s Doris Roberts that “there’s this wonderful new show, all about retirees in Florida—it’s called Miami Nice,” it was obviously a joke. Or was it?

In his 1992 memoir, The Last Great Ride, the late former NBC chief Brandon Tartikoff remembers spending a rainy afternoon channel surfing with his seven-year-old niece until they agreed on the 1953 Betty Grable–Lauren Bacall–Marilyn Monroe movie How to Marry a Millionaire. Tartikoff was struck by the idea: how about a frothy comedy about a group of women sharing an apartment together, waiting to meet Mister Right? There was just one problem: other people hated the idea, especially women. When he tried to recruit female writers to work on the project, they were offended at the idea of presenting the young, independent 1980s woman as being incomplete without a man. But the idea stuck in the back of Tartikoff’s mind, and later, while visiting his elderly aunt in Florida and observing her crotchety interplay with her neighbor, he had another inspiration: make it How to Marry a Millionaire for Women over Fifty.

“Brandon may not have shared those thoughts with us all, so I’m not sure how the How to Marry a Millionaire stuff ended up actually being connected to the development of The Golden Girls,” explains Warren Littlefield, who was then the network’s Vice President of Comedy Programs. But Littlefield does know that at what may have been the same time, the Miami Nice gag was gathering steam. “It had been the highlight of laughter in a long, boring shoot night,” he remembers. “That fall preview special had all these hot young stars from other shows, but here were these two middle-aged actresses who stood up in the spotlight and bam! They were sharp, they were hitting it, and they made their segment pop.” A week later at Los Angeles’s Century Plaza Hotel for the network’s off-site retreat, Littlefield, Tartikoff, and other executives tossed around ideas to develop into series for the 1985–86 season. As they recalled Diamond and Roberts’s phenomenal performance, suddenly “Miami Nice,” the shtick about the ridiculousness of a “retirees in Florida” sitcom, didn’t seem so ridiculous anymore.

From that meeting, Littlefield resolved to seriously develop Miami Nice as a sitcom for the following season. The timing was right to be daring. Only one season after turning around its comedy fortunes with the 1984 debut of The Cosby Show, NBC had nowhere to go but up. And having succeeded by airing Miami Vice—even though testing prior to the show’s debut had predicted horrendous ratings—the executives were ready to reach outside the 18-49 age group and defy convention one more time. “We felt like lightning had struck us with something,” Warren explains. “We would look at those little charts in USA Today, and there would be some factoid like ‘women over fifty have a one in eleven billion chance of remarrying.’ It was always some sad statistic, and it reinforced what we were feeling about ‘Miami Nice,’ that somehow, these women would be there for each other, and they would take a difficult reality and make a bright picture out of it.”

Although Roberts and Diamond were already committed to other NBC series, the network knew they would have no problem casting a show about older women. “We learned a lesson in casting The Cosby Show,” Warren remembers. “If we could have cloned Bill Cosby, then we could have created five more road companies of that show, because there was just so much talent from black actors who weren’t being used on television. And the same thing happened with this show. There was a large pool of wonderful older actresses who weren’t doing feature films and television, who were being ignored. And when we saw how similar that situation was to Cosby, we knew we were on the right track.”

A Gay Among Girls

BEFORE RECRUITING A writer for the project, the network decided that Miami Nice would center on household life for several women, one of whom owned the house. At least one character would be older, to allow for intergenerational conflict. And there would be one more character, a gay houseboy.

Yes, in 1985—twelve years before Ellen DeGeneres and her character Ellen Morgan’s courageous coming out on ABC’s sitcom Ellen, and thirteen years before NBC’s own Will & Grace, the first series created with a gay leading man—a major broadcast network commissioned a pilot that was to feature a gay character. “Miami at that time was such a cool, happening place, and a gay character just felt like someone you might find in that environment,” Warren explains. “To us, it didn’t feel bold or outrageous, but organic. These ladies are probably not on their hands and knees, scrubbing. They’ve had a lot of years where they’d done all that stuff, so they would hire someone to help out. And we thought the gay houseboy would be a fresh character and a fun contrast to the women.”

That all sounds logical—but as we all know, networks don’t always stand so tall against homophobia. In fact, just four years earlier at NBC, Tony Randall’s Sidney Shorr was to have been network TV’s first gay lead in the 1981–83 sitcom Love, Sidney, until internal network politics forced a change for the character. In the two-hour telemovie that launched the series, Sidney had been “not openly gay,” explains the network’s openly gay former Senior Vice President of Talent and Casting Joel Thurm. “But he was a lonely old man who had had a relat

ionship with a man we see in a picture on his mantel, and at one point he goes with Laurie, the young single mother who with her daughter moves in with him, to an old Greta Garbo movie, so it’s definitely implied.”

When the Love, Sidney movie turned out to the development execs’ liking, the future looked bright for a Sidney Shorr series. “But then,” Joel remembers, “someone at the network, obviously a rabid homophobe who didn’t want the project, slipped a copy of the movie to the network’s sales department without authorization. And so the sales department came into program meetings and announced that because of the gay content, they couldn’t and wouldn’t sell it to advertisers as a series. And if the sales department is one hundred percent against a project, that’s a very, very strong negative.” Eventually, out of desperation as many of its other series failed in the ratings, NBC did resuscitate Love, Sidney as a midseason replacement series—but not before turning gay Sidney Shorr into an asexual celibate. And that photo disappeared from the mantel, too.

Julie Poll, a television writer who worked as a production assistant on the series version, remembers NBC’s Standards and Practices department—a.k.a., the censors—combing through every word of Love, Sidney’s dialogue, eliminating any possible reference to homosexuality. “I’ll never forget. Laurie had a perfectly innocent line where she gratefully said to Sidney, who had taken her into his home, ‘You’re my fairy godmother.’ But then the network saw it, and out it went,” Julie remembers.

Enter Susan Harris

JUST A FEW years later, the proposed “Miami Nice” gay character might have suffered the same de-gayifying fate as Sidney Shorr. But, luckily for the houseboy, Littlefield got the idea through to writer Susan Harris, who had created one of TV’s first gay characters, Billy Crystal’s Jodie Dallas, on her first big hit comedy series, Soap. (Jodie may not have been the first regular gay character on American TV, but he was certainly the highest profile to date, since few remember Vincent Schiavelli’s Peter Panama on the short-lived 1972–73 CBS sitcom The Corner Bar.) But even the hiring of Harris happened by happy accident.

Paul Junger Witt and Tony Thomas—two-thirds of the then-growing TV powerhouse production company Witt/Thomas/Harris—had brought one of their writers in to present a new series idea about two young sisters living together to NBC’s Warren Littlefield. Littlefield had been unmoved by the pitch, but, eager to steal away the producers of such hits as Soap, Benson, and It’s a Living from rival ABC, he offered an idea of his own: how about you go off and develop “Miami Nice?” The writer—who is probably still kicking himself to this day—was uninterested. But just after seeing their scribe out of Littlefield’s office, Witt and Thomas poked their heads back through the executive’s doorway. “Were you serious about that idea?” they asked. Because Paul Witt had just the writer in mind.

Although she had sworn off writing for television after burning out during the intense production of Soap, Witt’s wife and producing partner, Susan Harris, was taken with the “Miami Nice” idea the moment her husband came home with it. “As soon as he used the word ‘older,’ that got me,” Susan remembers. “I love to write old people, because I find that the older the character, the better the stories he or she has to tell. So that was the hook for me—that I could write about an interesting demographic that had really been ignored.” Together, Witt, Thomas, and Harris, who had been a creative entity since the days of their first series, Fay, starring Lee Grant, for NBC in 1975, brainstormed the structure of the series: three women, a mother—and of course, that gay houseboy.

As Paul remembers, he and Susan Harris were more than happy to accede to the network’s request for a homosexual about the house. He notes that he, Susan, and Tony “had all grown up knowing gay people, and felt it was absurd not to see gay people on TV.” Soap had succumbed to cancellation after only its fourth season because, as Paul explains: “A phantom constituency [of conservatives] managed to convince Madison Avenue that they had more members than they did, and they would boycott.” But far from scaring the three producers away from gay characters and storylines, the Soap experience had “just made it all the more attractive to do it,” Paul reveals. “Not to rub anybody’s nose in anything. But we had been approached by more people about Soap’s Jodie character because he was the first out gay person they had seen, and he had made them feel much better about themselves.” So if there was indeed a risk to bringing another gay character to their new show, “it was a risk we wanted to take.”

The Golden Girls

A FEW MONTHS later, Warren Littlefield received delivery of a Susan Harris script, now titled The Golden Girls. The new name immediately started to grow on him. After all, the network had been wondering: How can we possibly risk confusing our audience by airing both Miami Vice and Miami Nice? But “girls”? “I had a moment where I wondered, ‘It’s the eighties. Can we call grown women girls?’” Warren remembers. “I brought that up to Paul and Tony, and they said, ‘Yes, Susan says we can say “girls.”’ And I said, ‘Okay—if she says so.’” And so, in that newly retitled script that NBC read and immediately loved, four Golden Girls named Dorothy Zbornak, Blanche Devereaux, Rose Nylund, and Sophia Petrillo were born.

2

MEETING (ALL)

THE GIRLS

“In the beginning, Brandon Tartikoff and the people at NBC all thought, ‘Let’s not go the tried-and-true way and just give America a bunch of familiar faces. Let’s go to Broadway and Chicago and cast some faces they don’t know.’ We thought that was odd, but we did then go out to those cities and see many, many, women—and nobody was quite right. After all, the stars we ended up bringing in were stars for a reason. It was just luck that they were all available for a series.”

—TONY THOMAS,

producer

TWO OF THE show’s creators, Susan Harris and Paul Junger Witt, remember how these four quite different ladies—Dorothy Zbornak, Blanche Devereaux, Rose Nylund, and Sophia Petrillo—sprang forth from the pilot’s pages.

Dorothy Zbornak

RECENTLY DIVORCED FROM Stanley, her philandering husband of thirty-eight years, brainy ex-Brooklynite Dorothy is a no-nonsense substitute schoolteacher. “Dorothy was the easiest character for us to come up with,” Susan explains. “Because Paul and I are from the New York metropolitan area. And she had a mouth on her.” And, Paul adds, “A sarcastic, cynical voice we could hear fairly early.”

Susan says she may have been conscious of the name Dorothy in honor of either Paul’s aunt or her own childhood friend. But the origin of the character’s unusual last name is much more clear: she cribbed it from her assistant, Kent Zbornak, who later became a producer on the show.

Rose Nylund

A WIDOW FROM the seemingly moronic town of St. Olaf, Minnesota, naïve Rose somehow finds the wisdom to counsel others at a grief center—that is, before beginning an even more unlikely career assisting a consumer reporter at a local TV station. “Rose, too, was a fairly easy character for us to create,” Susan remembers. “Because she sounded a lot like Katherine Helmond’s character, Jessica Tate, from Soap.”

Since Rose was to be of Scandinavian heritage, Susan borrowed the last name Nylund from a Swedish woman whom she and Paul had met sailing the Yugoslavian coast. “Rose was more midwestern than prototypically Scandinavian,” she says. “And there are a lot of names like that in the Midwest.”

Photo by WAYNE WILLIAMS.

Blanche Devereaux

A GEORGIA PEACH who never fails to remind her roommates that she is still ripe for the plucking, the hypersexual, über-Southern widow, Blanche, is the owner of the house in which the Girls live—all the better to entertain a steady stream of gentleman callers. “Blanche was definitely the hardest character for us,” Susan says. “We wanted very distinct characters, and that’s why we placed their origins in different parts of the country.” Problem was Paul and Susan hailed from New York Yankee territory, and Tony Thomas grew up in Los Angeles. So the trio turned to a reliable source: Southern

literature.

“Blanche is almost a literary figure in representing that classic kind of Southern femininity,” Paul explains. As Rue McClanahan remembers, Susan’s pilot script describes the character as “more Southern than Blanche DuBois,” her obvious namesake. “It’s an homage,” Paul says. “And certainly a way to remember which character was the Southern one.”

Sophia Petrillo

AN ESCAPEE FROM the fire-ravaged Shady Pines nursing home, the eightysomething Sophia shows up at daughter Dorothy’s door—and because she became so popular with viewing audiences, she never leaves. Sophia shows a tendency toward blunt honesty—caused, we’re told, by a stroke that destroyed the tactful part of her brain, yet left her with more than enough mobility to cause trouble.

As former New Yorkers, Paul and Susan say they had grown up with Italian friends and neighbors, and liked the “New York sensibility,” as Susan calls it, “either Italian or Jewish.” “It’s all very much the same,” Paul adds. “Except it’s probably less clichéd to show an Italian-American mother/daughter duo than a Jewish one.” Of course, this Brooklyn-bred Sicilian mama also knows her way around a knish, and her dialogue captures those cadences as well. She exhibits the best of both worlds because, as the half-Sicilian and half-Lebanese Tony explains, “The funniest rhythms in the world are Semitic. Sophia was Sicilian, but she has a lot of the comedy rhythms I grew up with as well.” In naming their pan-Mediterranean creation, Susan turned to her own childhood in Mount Vernon, New York, where the family name Petrillo “is a large part of Mount Vernon history.”

Golden Girls Forever

Golden Girls Forever